Dawn Eden recently published a wonderful book on the topic of healing from the wounds of sexual abuse. My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds with the Help of the Saints. This new publication follows her highly successful The Thrill of the Chaste: Finding Fulfillment While Keeping Your Clothes On. Dawn explains the inspiration behind her new book, as flowing from her experiences of speaking to people who had read Thrill of the Chaste. In that book she wrote of her own journey from a life of promiscuity to discovering the beauty and joy of chastity as opposed to the destructive dead-end that is lust. Dawn recounts how many who were not convinced by her arguments in Thrill of the Chaste were angry and hurt, feeling that she was judging them. She found that many of them had been a victim of sexual abuse at some time in their life. Dawn also experienced sexual abuse as a child and knows how abuse victims tend to blame themselves for what happened to them.

In an interview with AirMaria (21:00-ff) back in 2009, Dawn explained how it was that devotion to the Blessed Mother can be huge factor in bringing about transformation in a life plagued by sexual temptation. She relates that after she had written Thrill of the Chaste she would get into arguments on her blog with feminist bloggers over the subject Christianity and chastity specifically. Many times the feminist bloggers manifested a great deal of anger, which they directed at Dawn because they felt that she was judging them, or that Church, because of her doctrine on chastity, was judging them. Ironically, because Our Lady and purity are so closely identified, she also found that those living and impure life also had an aversion to Marian devotion. But the purity of Our Lady is not a judgment, but a living fire that is purifying, liberating and welcoming. If the just father embracing his prodigal son is the image of Divine Mercy, then the Immaculate Virgin Mary is the image of pure love delivering us from selfishness and at the same time showing us unconditional compassion. This is the Marian message that we need to communicate to the world about chastity.

One of the great attractions of devotion to Our Lady and, in particular the sacramental of the Miraculous Medal, is the compassion of Mary, who as Mother of Jesus is also our Mother, and who is present to Her children not to judge but to nurture, heal and affirm. This was exactly the attitude of St. Maximilian Kolbe, who knew that the Blessed Mother was the easiest way to God, precisely because She is pure, pleasing to God and does not judge the sinner. He used to give out the Miraculous Medal to souls in need because he simply wanted to introduce the presence of Mary into their lives.

I often think of this power of Our Lady, resplendent and transformative as the Way of Beauty. Our Lady is both Icon of all that we hope to be and Mother of our soul, bringing to pass a transformation from sin to grace that we are too broken to accomplish ourselves.

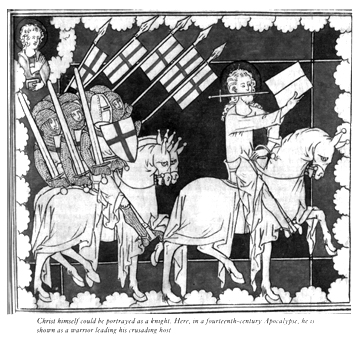

In My Peace I Give You, Dawn points out that although the Immaculate Virgin underwent no purification, sinless as She is, Mary does have a wounded heart through which She is uniquely associated with the suffering of Her Son. It is an interior wound that lays bare the secret of hearts (cf. Lk 2:35). Our Lady knows the pain of Her children, and She holds them in the piercing of Her Heart. This is the realm of mental suffering, where all pain is synthesized and either accepted or rejected, where the human condition is placed in the crucible of God’s love and divine, sacrificial and suffering love is rarefied and separated from the suffering of sin and darkness and fear. Christ underwent both a physical and mental suffering in the agony of his Passion. Blessed John Henry Newman called this the “double agony” of Christ. But it was the mental suffering of Our Lord that gave form and purpose to the rest. Our Lady is particularly iconic of this mental suffering, because Hers is a suffering of “compassion.” She suffers with the One who suffers because She loves Him and is present in His sufferings.

In a particular way Dawn points to the faith Our Lady exercised after Our Lord’s Ascension—a time in which She had only the memories, the mental images of Her Son’s death and resurrection, but continued with the rest of the Church to participate in these mysteries though the veiled but transformative presence of Our Lord in the Eucharist. In the Heart of Mary, especially in that Heart which is a tabernacle for the Eucharistic presence of the Sacred Heart of Her Son, all memory is recapitulated and recirculated. Everything that hurts is given a meaning beyond itself and all who suffer experience both the Passion and Resurrection of Christ as the purpose of their lives and the means of their own healing.

With Her new book, Dawn has taken these ideas to the next step, as a kind of bridge between our own brokenness and the immaculate integrity of the Blessed Virgin. The saints underwent the transformation from the brokenness of original sin, the history of sin within their families and their own lives, to healing and re-creation in Christ Jesus. As Dawn points out, some of them experienced even the wound of sexual abuse, and subsequently had to struggle against great odds to live authentic spiritual lives. The stories of the saints, thus offers us who are broken the encouragement we are looking for and the powerful presence upon which we can rely:

No matter what evil was done to us, if we, like the saints, offer our hearts to God, he will take us as we are, with all our past experiences. Our hearts right now contains all the raw material Jesus needs to mold them so that, with his grace working over the course of time, they may become like His. This is true no matter how damaged we may feel. So long as our hearts long for union with Jesus’ Sacred Heart, our feelings about ourselves will not prevent such union, because God’s love is stronger than feelings. It is a presence.

Reading about the lives of the Saints is not just about seeing their example and figuring out how to imitate them, or how to integrate the teaching of Christ in a practical way. It is all that, and more. As we are taught in Lumen Gentium 50:

Nor is it by the title of example only that we cherish the memory of those in heaven, but still more in order that the union of the whole Church may be strengthened in the Spirit by the practice of fraternal charity. For just as Christian communion among wayfarers brings us closer to Christ, so our companionship with the saints joins us to Christ, from Whom as from its Fountain and Head issues every grace and the very life of the people of God.

The saints are living members of our family who are present and who teach from within because we are one with them in prayer, and because they intercede with God on our behalf. We identify with their brokenness. We aspire to their victory. But we also know that they are on our side, fighting on our behalf. We need a new set of memories in order to overcome the pain of the past, active memories like the commemoration of the Mass by which we participate in purity itself. We need also the active memory of Our Lady who ponders in Heart the mysteries of the faith She witnessed with Her own eyes, and the active memory of the saints who have accomplished the transformation we all long for and so desperately need.

In her book, Dawn writes much about memory and its healing, even of the memories of things that have been so painful that we have buried beneath our consciousness. She quotes Pope Benedict: “Memory and hope are inseparable. To poison the past does not give hope: it destroys its emotional foundations.” The parallel between memory and the theological virtue of hope is very Bonaventurian. St. Bonaventure also aligns memory and hope with the First Person of the Blessed Trinity, the Father. How much sexual abuse today is somehow related to either the abuse of a father or at least the dereliction of the duty of a father. Perhaps these are the toughest memories of all. And that is why we need all the help we can get from the friends of Jesus to get us back to the embrace of our merciful Father, who alone can heal us.

Dawn has done another great service to the Church and to souls who are in need of encouragement and healing. May God bless her for it.

Yesterday I met with the Knights of Lepanto and, among other things, I spoke to them about Our Lord’s agony in the garden. I read to them from the exquisite meditation on that subject by Venerable John Henry Newman, entitled

Yesterday I met with the Knights of Lepanto and, among other things, I spoke to them about Our Lord’s agony in the garden. I read to them from the exquisite meditation on that subject by Venerable John Henry Newman, entitled