The Spirit of Lepanto is greater than the history in which it is rooted. The recounting of the historic of battle that took place on October 7, 1571 lends itself to the genre epic literature. The events of that day call for a bard like Chesterton to cast words into the cadence of drum and cannon:

Don John’s hunting, and his hounds have bayed—

Booms away past Italy the rumour of his raid.

Gun upon gun, ha! ha!

Gun upon gun, hurrah!

Don John of Austria

Has loosed the cannonade.

And I still get chills, when for the thousandth time I read the words:

. . . O Lady of Last Assurance,

Light in the laurels, sunrise of the dead,

Wind of the ships and lightning of Lepanto

In honour of Thee, to whom all honor is fled.

I pray that what gives me chills is the true Spirit of Lepanto, and that it does much more than give me chills.

I have always secretly lamented the fact that the Feast of Our Lady of Victory was changed to the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary and that the language of even the traditional collect for the present feast is void of the bellicose. We are all familiar with the prayer. We use it every time we pray the Holy Rosary.

I have much preferred the collect for the Mass Contra paganos (against the heathens), euphemistically englished in the hand missal “Mass for the Defense of the Church”:

Almighty, everlasting God, in whose hand are the strength and man and the nation’s scepter, see what help we Christians need: that the heathen peoples who trust in their savagery may be crushed by the power of Thy right hand. Through our Lord Jesus Christ. . .

I really don’t question the wisdom of Holy Mother Church in this regard, but I do think that in this feast we have an opportunity to consider with a contemplative mind the Spirit of Lepanto or what Professor Roberto de Mattei calls a “category of the spirit”:

As heirs of Lepanto, we should recall the message of Christian fortitude which that name, that battle, that victory have handed down to us: Christian fortitude, which is the disposition to sacrifice the good things of this earth for the sake of higher goods—justice, truth, the glory of the Church, and the future of our civilization. Lepanto is, in this sense a perennial category of the spirit.

It seems to me that this category of the spirit is transhistorical. It is the recapitulation of the protoevangelium:

I will put enmities between thee and the woman, and thy seed and her seed: she shall crush thy head, and thou shalt lie in wait for her heel.

It is all right there. That is why Genesis 3:15 is called the first gospel (protoevangelium). Everything that comes after is all fulfillment, partially at first by way of types (Judith, Esther and the Ark, for example), and then in the fullness of time the Woman and Her Seed bring all things to fulfillment, waging war against the Dragon on the top of the world in the greatest eucatastrophe of all time.

St. John’s vision on Patmos of the Woman gloriously arrayed with the lights of heaven, but militantly in travail, projects into the past, present and future the tribulations of the People of God. The birth pangs are not of Bethlehem, but of Calvary. It was only at the foot of the Cross that the Virgin suffered in the throws of delivery. But surely there is an intimation of Bethlehem in this reference to birth, just as there must be an allusion to the flight into Egypt in the words And the woman fled into the wilderness (v. 6), though the primary reference is the cosmic battle with Satan and the rest of the fallen host.

But St. John was also speaking to the churches of his own time that were suffering persecution and were plagued by heresy. In the breathless voice of the Holy Spirit, the Apostle proclaims: He that hath an ear, let him hear what the Spirit saith to the churches.

But it is more than that. The Woman is the promised Victrix, Mary the New Eve, dolorous and glorious, in Her earthly adventure and in Her heavenly reward. She also represents the churches, the direct recipients of St. John’s revelation, addressed directly in his cover letters to the seven churches. But She is also the Church Militant of every age that suffers persecution and is plagued by heresy. Further still, the macrocosm of the Church Militant is reflected in the microcosm of each and every soul, where the Woman and the Dragon contest each other’s dominion.

Lepanto is a parable, a recapitulation of the protoevangelium, just as are the history of Judith and Mary and the churches which St. John addressed. But so are the chronicle of the Battle of Viena, and the Epics of Tepeyac and Rue du Bac, and more poignantly for our own day, the prophetic history and parable of the Acts of Our Lady of Fatima. These are the macro-eucatastrophes of the ages, which spell out in the sky, in the medium of light and miracle, the even more fundamental reality of the micro-eucatastrophes (hopefully) going on within our moral and spiritual lives.

The hateful spirits of, pride, greed, lust, anger, gluttony, envy, and sloth claw at the doors of our hearts, or worse, live within them. We are kingdoms under siege or kingdoms fallen. We make so much of the macro and so little of the micro and for that we are recipients of the terrible apocalyptic reprimand:

But I have somewhat against thee, because thou hast left thy first charity. Be mindful therefore from whence thou art fallen: and do penance and do the first works. Or else I come to thee and will move thy candlestick out of its place, except thou do penance (v. 4-5).

Perhaps I am all washed up for my secret regret. Perhaps the Church knows better than I. Of course she does! The collect for today’s feast and for every Rosary asks for the grace to transform the vision of truth seen through the eyes of the Victrix into Her very life within us: that meditating we might imitate. That is the fundamental art of war upon which all strategies and tactics depend. Perhaps the bellicose language has been pealed away from the orations because we tend win a few of the battles we do see, while loosing the war we do not see. The Third Part of the Secret of Fatima is bellicose and macro enough, but it all hinges on individuals, and therefore on praying and living the Rosary more than anything else.

Both St. Pius V and Don Juan prayed the Rosary. Together they were victorious, inside and out. Men of Prayer and Action, yes, but in all in its proper order. The Third Part of the Secret at Fatima refers to realities both micro and macro and in that order.

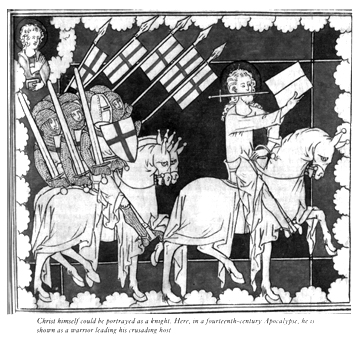

The Spirit of Lepanto is the Spirit of Mary Victrix. It (She) is a living ideal that communicates itself (Herself) from Heart to heart. It is vital and preeminently dangerous, boundless and indomitable. It is also the Spirit of the White Horse, upon which rides the KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS, whose head is crowned, whose eyes are fire and out of whose mouth comes a sharp two-edged sword. The Woman of chapter 12 is the Lady, who girds of the Knight in chapter 19 of St. John’s revelation. And together they constitute a power, beyond which cannot be conceived.

The great prophetic grace of our age is the message of the modern Marian apparitions, which, as already said, are recapitulations of the protoevangelium, but with this twist: we live in the most apocalyptic age and the urgency of the prophetic plea for devotion to Her Immaculate Heart is the voice of the Spirit speaking to the churches right now! St. Louis de Montfort says of the Marian Apostles of the Latter Days that

[t]hey will be ministers of the Lord who, like a flaming fire, will enkindle everywhere the fires of divine love. They will become, in Mary’s powerful hands, like sharp arrows, with which she will transfix her enemies (56).

The enemies of Mary are, in a sense, transfixed with the same sword that has pierced Her heart. Her apostles know the point of that sword all too well, with memories both bitter and sweet. It is swordplay that is well-landed upon both friend and foe.

Fatima is a modern-day apocalypse. No wonder there in October the Woman revealed herself to be Our Lady of the Rosary and was clothed with the whirling sun. It’s spirit is the Lepanto of our age, that transhistorical category of the spirit that is both the first promise to mankind and the patrimony of this last age. However we name this Spirit, it is bigger than the histories in which it enshrined and deeper than the hearts in which it works itself out.

We can continue to bang out solutions of our own contriving that satisfy our egos, like clever soundbites and slogans, and rely on rhetoric and imprudent zeal, or we can look into the skies, indeed, into the Temple of God and make all things according to the pattern shown us on the mount (cf. Hebrews 8:5). If we do not see this vision and strive to embody it in our own lives, we have not understood, or have refused to understand the parable of Lepanto and the spirit of this feastday.

If you have not made the consecration to the Blessed Virgin, I pray you do, and soon. Don’t only pray the Rosary, live the Rosary.

Oremus pro invicem, and sing

I cast myself before Thee, Thy bondsman and Thy fool;

Thy patronage is freedom, Thy slavery my school.

I offer Thee my sword hilt and wait for Thy command

To serve among Thy servants who pledge to take a stand.

That I might die in battle, a victim of Thy love:

My wish, my prayer, my promise, thus written in my blood.

I saw the bark of Peter ride dark into the sun,

But darker still the marking of crescent, hoard and gun.

Her sails lay flat and mellow, Her men had pledged their troth,

Left hand on beaded psalter, the right to keep their oath.

The haughty fiend had counted on fear to win the day,

But Thine own breath has countered to turn the wind their way.

My Queen, to Thee be honor and praise through all Thy knights

Who toiled and bled and parted Thy martyrs robed in white.

All courtesy and prowess, all strength and gentleness,

Thy heart a pyx of virtue, Thy face all loveliness.

Then at the hour of judgment my colors Thou may see,

Thy Son upon His white steed, Thou pray to come for me.

Happy Feast of Mary Victrix.