True knighthood is the Holy Grail of manhood, a revelation attainable only by the pure. The proud are ever barred from taking a draught from it.

Our very captivation with the Holy Grail consists in the fact that it has not been found and only few have even seen it. And, of course, the reason that the mysterious cup remains ever out of reach for the ordinary man and is because its quest is fraught with danger: fearful obstacles, inscrutable riddles, and deadly foes.

To those who possess true manliness, such obstacles are the reason why The Quest is so appealing. By definition manliness is the penchant to overcome obstacles. The more hopeless the attainment, the bigger and better is the man who laughs in the face perils to be found there. Those who are lesser men still aspire to the Grail, but fear leads them to experience the danger only vicariously by following along at a safe distance, through spectator sports, litrerature and movies.

And yet there is a temptation in that boldness to which those gallant men of the Round Table too easily succumb. The bigger and better that a man thinks he is, the more likely he is to fail utterly in attaining the goal. Gawain, for example, showed himself the fool for this very reason. And Lancelot had to be taken down a few notches (many actually) before he was even granted a partial fulfillment of his desire. Galahad attained the grail, not so much by his prowess, but more so, by his humility and purity.

There is a strange and wonderful coincidence of opposites in the embodiment of true chivalry: courage, strength, boldness and skill, on the one hand; reverence, humility, meekness, and deference on the other.

In a sermon written during his Anglican Period, entitled, “The Weapons of the Saints,” Venerable John Henry Cardinal Newman couched the spiritual life in terms of a war in which the stratagem for victory demands an inversion of worldly values:

But in that kingdom which Christ has set up, all is contrariwise. “The weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strongholds.” What was before in honour, has been dishonoured; what before was in dishonour, has come to honour; what before was successful, fails; what before failed, succeeds.

It is this inversion that constitutes the real difficulty to the attainment of the Holy Grail of true knighthood. It is the riddle of riddles. The Black Knight, enemy of our souls, guards the bridge that leads to the hermit who is ensconced away from the manners of worldly men. It is from him that we are to unlearn our pride and find the real weapons by which we are to succeed in our quest.

Cardinal Newman’s sermon is a commentary on Our Lord’s words: Many that are first shall be last, and the last shall be first (Mt 19:30). And he supports his thesis from many other passages of the New Testament concerning, for example, strength made perfect in weakness (2 Cor 12:9), the of putting down the proud and the exalting of the humble (Lk 1:52), the blessedness of those who suffer and the woes of those who are satisfied (Mt 5:2-10; Lk 6:24-26), and God’s choice of the weak and despised to do his work (1 Cor 1:27). It should be abundantly clear to anyone with a modicum of familiarity with scripture that God triumphs in and through those who have rejected worldly ambition and self-assuredness.

The invisible powers of the heavens, truth, meekness, and righteousness, are ever coming in upon the earth, ever pouring in, gathering, thronging, warring, triumphing, under the guidance of Him who “is alive and was dead, and is alive for evermore.”

Truth, meekness and righteousness, according to Venerable Newman, are the real weapons of the saints, the means by which they are victorious over Satan, sin and death. The Holy Grail of Christian Knighthood is so hidden that in order to find it the knight must lose himself in the process.

This is that intangible, greater thing, after which young men aspire. It is the stuff of true nobility. It is strength without arrogance, command without self-interest.

Venerable Newman notes that “we like to hear marvellous tales, which throw us out of things as they are, and introduce us to things that are not.” The paradox of the cross and of the victorious King who triumphs through His own death is the cosmic myth, the retelling of which is the incantation that opens the sealed doors of our hearts. He that openeth and no man shutteth, shutteth and no man openeth, is the only one with the key (Ap 3:7).

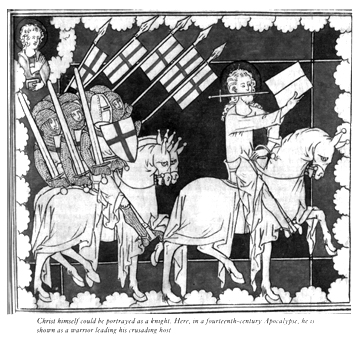

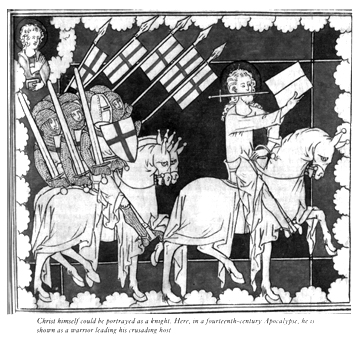

The beloved disciple saw Him mounted on a white horse, and going forth “conquering and to conquer.” “And the armies which were in heaven followed Him upon white horses, clothed in fine linen, white and clean. And out of His mouth goeth a sharp sword, that with it He should smite the nations, and He shall rule them with a rod of iron.” [Rev. xix. 14, 15.]

The Quest of the Holy Grail is a lesser myth, as are all other stories when compared to the gospel myth in which the most fantastic tale is merged with history, and where what Tolkien called eucatastrophe, a literary climax beyond our wildest hopes, is made the substance of all our hopes and the ground upon which we walk in the daylight of this world.

Indeed, the return of the king in Tolkien’s mythology is an ascendency by way of descent. Aragorn and the Dúnedain are content to be despised if that will better equip them to protect and defend the peoples of Middle Earth. Aragorn himself must choose the path leading downward, literally underground, through the Paths of the Dead under the White Mountains, like Christ in His harrowing of hell, if he is to triumph on behalf of those entrusted to his care.

After Gandalf had “passed through fire and deep water,” and had completed his own christic transformation, he delivered a message to Aragorn from the Lady of Light, Galadriel:

Where now are the Dúnedain, Elessar, Elessar?

Why do thy kinsfolk wander afar?

Near is the hour when the Lost should come forth,

And the Grey Company ride from the North.

But dark is the path appointed for thee:

The Dead watch the road that leads to the Sea (Book III, Chapter V).

Aragorn chose the path of truth, meekness and righteousness. He was prepared to face his fear, and he was not afraid to confront his own ego with the double-edged sword of God’s truth. He chose to go down in order to go up, to be last in order to be first. Yet the myth of Aragorn cannot be a vicarious substitute for our own humiliation. We must really experience it. Newman has it right:

We so love the idea of the invisible, that we even build fabrics in the air for ourselves, if heavenly truth be not vouchsafed us. We love to fancy ourselves involved in circumstances of danger or trial, and acquitting ourselves well under them. Or we imagine some perfection, such as earth has not, which we follow, and render it our homage and our heart. Such is the state more or less of young persons before the world alters them, before the world comes upon them, as it often does very soon, with its polluting, withering, debasing, deadening influence, before it breathes on them, and blights and parches, and strips off their green foliage, and leaves them, as dry and wintry trees without sap or sweetness.

We must not loose our idealism as we grow older, but “heavenly truth” should purify our tendency to experience knighthood vicariously through its trappings and shards. Ours is to be the knighthood of the real Dúnedain, a hidden knighthood in search of the hidden, but very real Holy Grail.

As a Franciscan, I have had many opportunities to reflect upon the militant example of Saints Francis and Maximilian, and of the great tertiary St. Louis of France. The Holy Patriarch of the Seraphic Order, Our Holy Father St. Francis, was well aware of the Arthurian legends and aspired to knighthood and the Holy Grail himself. Later, after he too had chosen the path downward, he called the simple brothers who lived in seclusion and despised status and pomp, his “Knights of the Round Table.”

In this last week of ordinary time, during the “octave” of the Feast of Christ the King, we look for His return at the end of the world, when he will preside over the cosmic resolution to the perennial struggle of St. Michael and the dragon. Then He will raise his wounded hands over the universe and all of us will be witnesses of the full revelation of His truth, a more powerful illumination than possession of the Grail itself. Then we will all know what true chivalry is and whether we are worthy to drink from the cup filled by the hands of Him who carried the sword of truth and slayed the dragon by His humble acceptance of our condition and by His willing suffering and death.

The weapons of the true knight are those of the saints: truth, meekness and righteousness. They are best fitted to help us along the way of our Quest, a path that leads up a narrow crag in a mountain. But this path to the heights strangely leads us downward by many uneven steps, until we arrive in the sanctuary of the Holy Grail and find rest in the yoke of Christ on the Holy Mountain of His Passion, Death and Resurrection.